Introduction to Lesson 2

The practice style of dermatologists differs from that of many physicians. In part, this is because dermatology is extremely remunerative–primarily because elective procedures, such as cosmetic procedures, represent a significant percentage of many dermatology practices, with some practices focusing almost exclusively on these procedures. These services are paid for directly by patients, in full, and often in advance. For this reason, some dermatologists can work 3- or 4-day weeks and still earn in the highest percentages of all physicians.5 As a result, dermatology attracts some of the top medical school graduates–and regardless of whether the focus of a dermatologist is on serious skin conditions or cosmetic procedures–they represent the “cream of the crop” when it comes to education and training.5

In this lesson, we will examine some of the key practice characteristics of a typical dermatologist. Note that here, we will focus on a diverse practice, rather than a cosmetic dermatology-focused practice.

Where Do Dermatologists Practice?

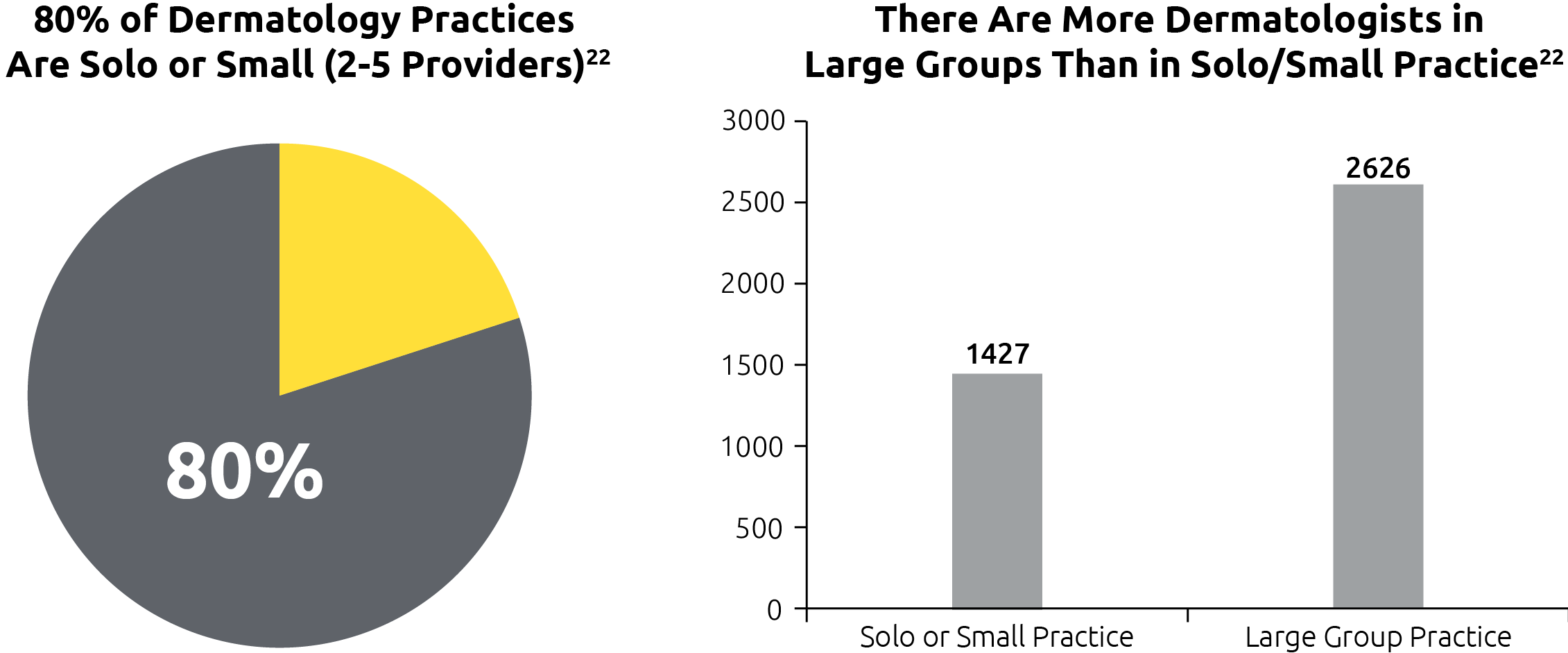

Unlike other areas of medicine, the private practice model is still common in dermatology.5 In a 2017 study leveraging Medicare data (and thus not fully representative of the complete dermatology workforce), solo and small (2 to 5 providers) practices accounted for more than 80% of dermatology practices. However, when viewed at the level of the number of dermatologists in private or group practice, there were almost twice as many dermatologists in large groups (2626) than there were in solo practice (1427). It appears that dermatology is trending toward the large practice model slowly, with a 12% increase in the number dermatologists working in large groups occurring between 2012 and 2017.22

Where Do Dermatologists Practice? (Continued)

In total, across the entire United States, there were 11,003 dermatologists in active practice in 2017, or only about 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 people.22 The number of dermatologists per 100,000 people varies somewhat by region from a low of 3.11 per 100,000 in the Midwest to 4.39 per 100,000 in the Northeast.22

Across all regions, the demand for dermatologists is high, as evidenced by wait times for appointments: on average, a new patient can expect to wait at least a month for a first appointment, and even established patients must make appointments at least 2.5 weeks in advance.23

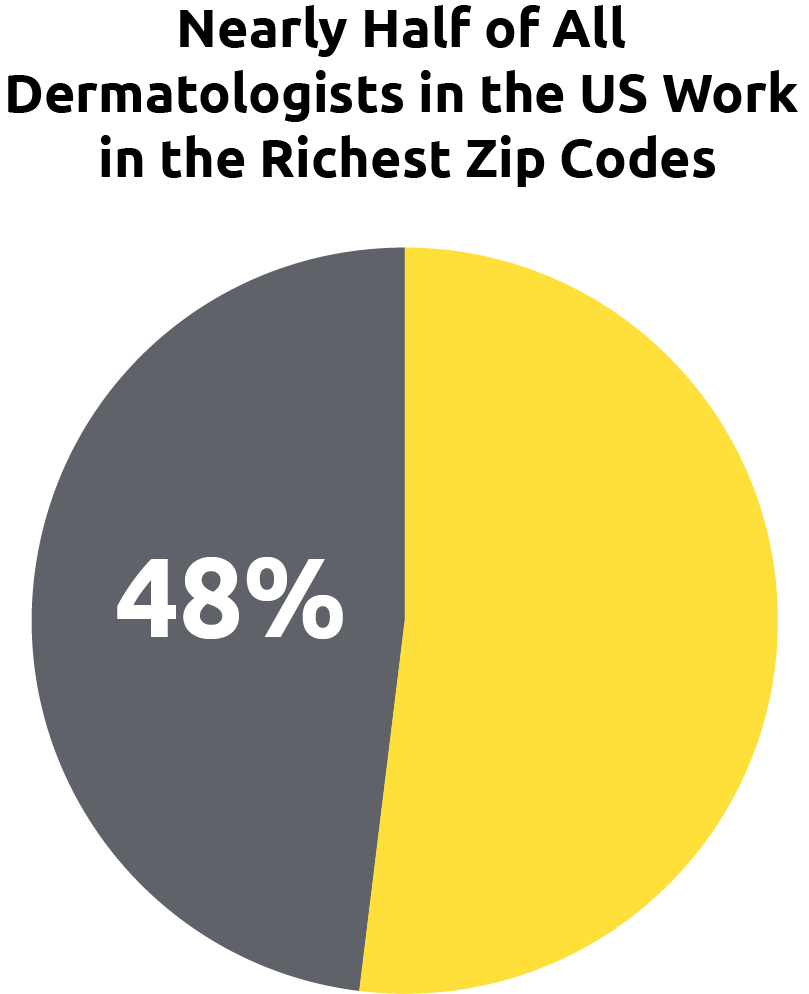

Importantly, there is substantial variation in the number of dermatology practices based on income levels of various zip codes. About 48% of dermatologists nationwide work in the richest zip codes, while only 18% work in the poorest zip codes.22 Paralleling this trend, there is a shortage of dermatologists in rural and so-called “mid-market” areas.5

Dermatology Practices: The Rural-Urban Divide

The typical dermatology practice varies by location.

Dermatologists in rural and midmarket regions tend to spend more time diagnosing and treating serious skin problems, like psoriasis, cancer, and fungal infections, and much less time providing cosmetic services. They thus must spend more time with each patient treating difficult cases and are more exposed to malpractice suits.

Dermatologists may be difficult to recruit in rural and midmarket regions. For this reason, many of these communities recruit dermatology nurse practitioners, dermatology physician assistants, or primary care physicians with some training or experience in dermatology to fill the gap.5

In contrast to rural and mid-market dermatology practices, dermatologists in urban practices can often see as many as 50 to 60 patients per day because they have relatively more cosmetic-focused practices. In these practices, nurses, physician assistants, and even aestheticians may work up many patients and provide some treatments, with the dermatologist supervising–much like how a dentist's office operates.5

Dermatology Practice Type Breakdown

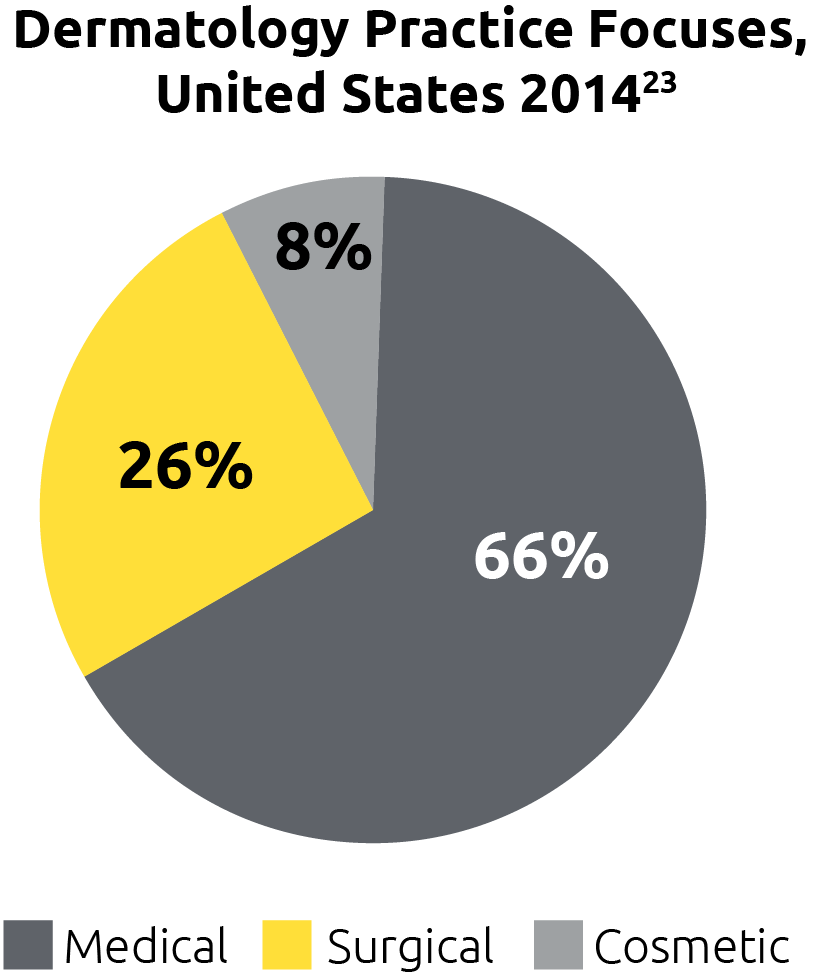

The majority of dermatology practices are “medical” practices. These focus on the “disease” aspect of dermatology, meaning that they focus on addressing medical conditions affecting the health and appearance of skin in patients. Medical dermatologists are the main type of dermatologist that psoriasis patients see.23,24

Another quarter of practices are focused primarily on advanced surgical interventions, such as Mohs surgery. In general, patients with psoriasis and no other skin conditions do not require care from these physicians.23

About 8% of practices are focused primarily on cosmetic procedures—for example, Botox injections, chemical peels, laser hair removal, and vein reduction.23,24

The Practice of Dermatology

Now that we've covered the training of dermatologists, the other types of advanced practice healthcare providers in the office, and the role of medical assistants/nurses, as well as the key characteristics of their practices, let's take a closer look at the actual practice of dermatology—the exams, conditions, and procedures that many general dermatologists and advanced practice healthcare providers perform. Here, we will focus on the typical duties in a general dermatology practice, as the way that a cosmetically focused practice is run and the types of treatments and procedures administered is very different from those in a medically focused office.

The Practice of Dermatology: Skin Exams

The total body skin exam (TBSE) is the foundation of dermatologic practice.25 It is performed to25:

- Identify potentially harmful lesions of which the patient is potentially unaware (such as skin cancers and pre-malignant lesions)

- Reveal hidden clues to diagnosis, for example, psoriasis plaques on the buttocks or gluteal cleft

- Inform counseling on sun protection measures–for example, the presence of sun damage may suggest the need for improved skin protection

The TBSE is always indicated in new patients with an undiagnosed skin condition, and it is also an integral part of the ongoing follow-up of patients with extensive skin conditions, such as psoriasis.25

The Practice of Dermatology:The 10 Most Common Medical Conditions Seen in the General Dermatology Clinic

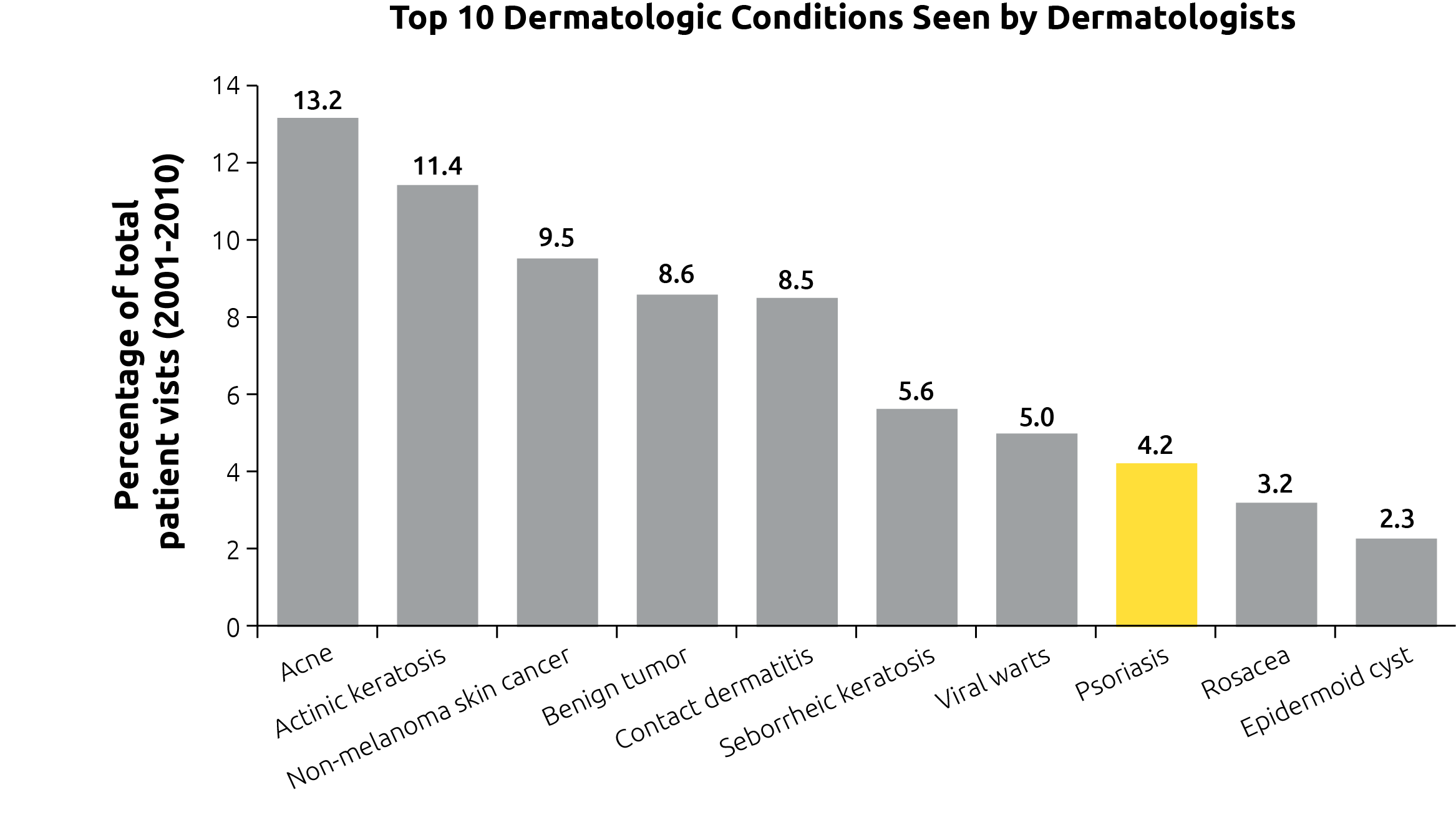

As noted above, dermatologists can identify and treat more than 3000 conditions.1 While there are some clinicians with a particular experience and interest in managing patients with psoriasis, in the average medical dermatology clinic, psoriasis only accounts for about 4% of patient visits. Nevertheless, this places it among the top 10 conditions seen by medical dermatologists, in terms of number of visits.26

The Practice of Dermatology: Dermatologists Are Also Proceduralists

Medical dermatologists also perform a broad range of minor surgical procedures. More extensive surgical interventions, including Mohs surgery, are performed by procedural dermatologists (discussed in Lesson 1). Setting aside cosmetic procedures, some of the procedures performed in a medical dermatologist's office include:

- Various types of skin biopsies. Shave biopsies remove a superficial slice of growths or lesions; punch and excisional biopsies remove larger amounts of the lesion, or even the entire lesion, and generally require stitches27

- Cryosurgery. This procedure involves using liquid nitrogen to freeze and destroy single or multiple growths27

- Photodynamic therapy, which involves application of light-activated chemicals to treat lesions27

- Electrodessication and curettage, which involves scraping away the growth with a curette and application of electrical current to stop the bleeding27

Teledermatology

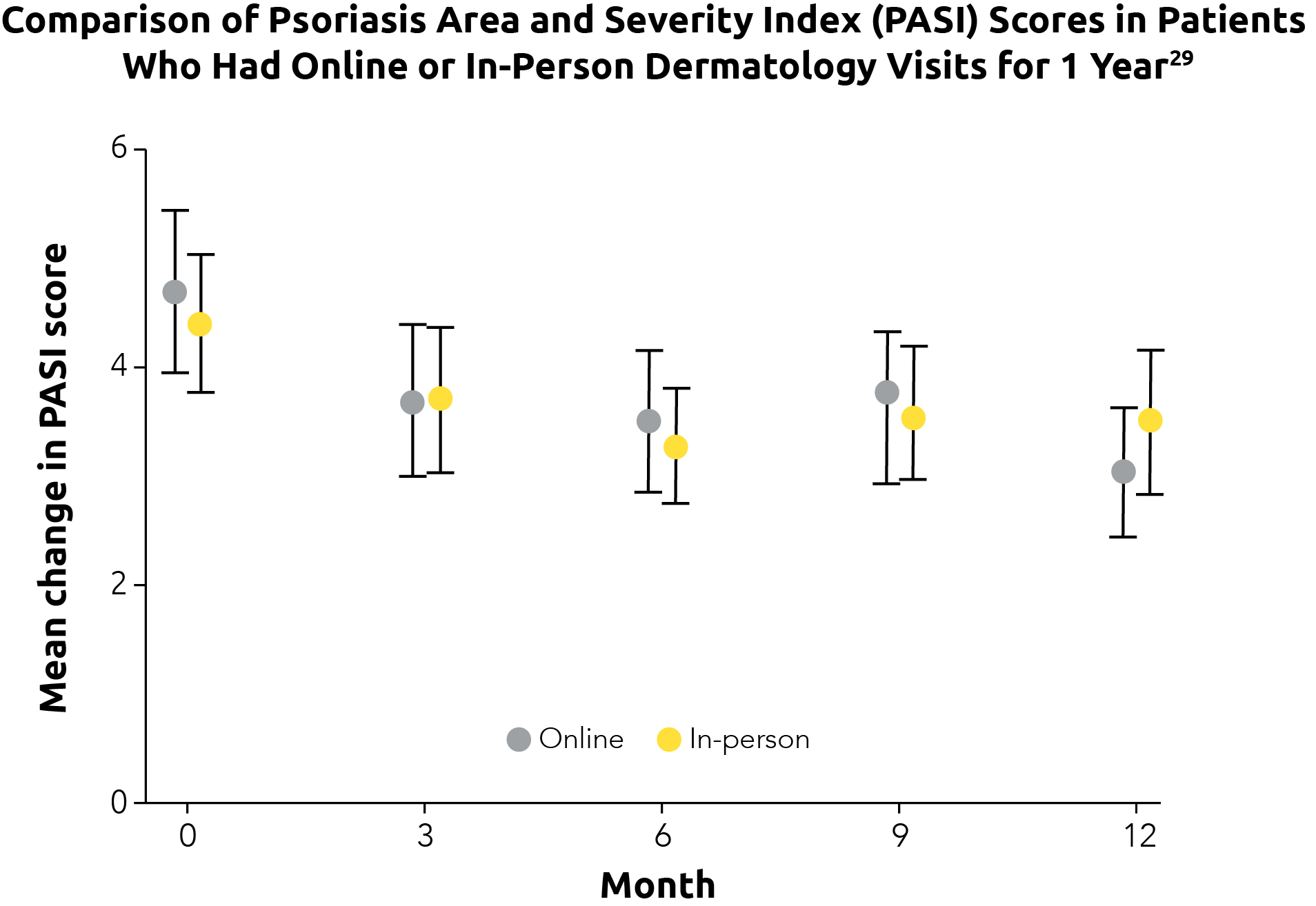

Telemedicine encompasses a wide range of technologies that allow patients to “visit” their provider without the need for a clinic visit. It can be as simple as emailing photos to the healthcare provider or having a phone conversation to as complex as a live video chat.28 A study of teledermatology conducted in 2015-2017 found that improvements in clinical outcomes in patients with psoriasis were similar whether they were seen in person or had an online visit with their provider via photographs.29

Data from a large-scale survey of dermatologists in 2014 found that the use of telemedicine was relatively limited, with only 11% of practices routinely seeing patients using this modality.23 Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the practice of teledermatology has increased substantially; in fact, one clinician estimated that his clinic saw 10 times as many patients via telemedicine in a single month in 2020 than they did in the entire previous year.28 It remains to be seen whether the trend toward teledermatology will continue after abatement of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many Patients With Psoriasis Are Managed in Primary Care

It is important to recognize that, while dermatologists often take the lead in managing psoriasis, some patients may be primarily or completely managed by primary care providers. Although no recent studies exist, a cross-sectional survey of National Psoriasis Foundation members, published in 2013, found that approximately 22% of patients were treated by primary care providers and 78% were at least evaluated by either a dermatologist or a rheumatologist (in the case of suspected psoriatic arthritis).30 21.4% of patients surveyed cited high cost as a reason for not consulting specialists for care of their disease.30

While it is feasible in some cases for primary care clinicians to manage patients with psoriasis, there are many situations in which referral to a dermatologist is recommended, including3:

- When confirmation of the diagnosis is needed

- When the response to treatment is inadequate, as measured by the clinician, patient, or both

- When there is a significant impact on quality of life

- When the primary care clinician is not familiar with the treatment modality recommended, such as UV therapy, phototherapy, or immunosuppressive medications

- When the patient has widespread severe disease

- In cases where the patient has psoriatic arthritis, referral and/or collaboration with a rheumatologist is important

The National Psoriasis Foundation recommends that all patients with psoriasis be seen by a dermatologist, although the foundation recognizes that, because of location or insurance plan, some patients may have to be seen by a primary care clinician.31

Support Staff in the Dermatology Office

Now, let's look at some of the critical support personnel in the dermatology office.

Biologics coordinators: Biologics play an important role in the management of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Biologic coordinator is an individual (sometimes more than one) within the dermatology office who manages the patient journey from prescription to drug acquisition. In addition to drug and disease education, these staff communicate with insurance providers, complete enrollment forms, review benefit verifications, submit prior authorizations, write appeals and letters of medical necessity, direct patient assistance and bridge programs, and coordinate specialty pharmacies and manufacturer hubs.32

Reimbursement specialists perform many of the same duties as biologics coordinators, but are focused on all treatments, rather than biologics specifically. Reimbursement specialists, work with insurance and billing companies to process medical reimbursements for patients. Their primary job duties include interacting with patients, managing financial documents, transcribing medical records, communicating with insurance providers, and assisting with other administrative tasks. Some reimbursement specialists may have a professional certification in medical billing.33

Dermatology 101: Summary

Select each of the cards below to review key information from this lesson.

Who Are Dermatologists?

- General dermatologists see a wide range of conditions and can treat patients both medically and surgically4

- Dermatologists manage both the pathologic and cosmetic manifestations of skin disease, and play a central role in normal skin care, skin cancer prevention, and sun protection4

- Dermatologists have extensive training, including 4 years for a bachelor's degree, 4 years of medical school, an internship of at least 1 year, and a minimum of 3 years of residency1

- Dermatologists may be general dermatologists, or may have subspecialties in dermatopathology, procedural dermatology, or pediatric dermatology5

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are an integral part of the care paradigm at many dermatology clinics; both of these healthcare providers can perform procedures and prescribe10,18

The Dermatology Practice

- For many reasons, dermatology is an attractive career choice for physicians, and, as such, it attracts top medical school graduates5

- The solo/small practice model remains common in dermatology, representing about 80% of practices22

- The largest concentration of dermatologists is in urban areas; in other areas, patients with skin conditions may be managed by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and primary care physicians5

- The majority of dermatologists are general dermatologists (66%), a smaller percentage are surgical (26%) or cosmetic (8%) dermatologists23

- Dermatologists are trained to recognize several thousand diseases, some of which are quite rare. Psoriasis accounts for about 4% of clinic visits and it is the eighth most common skin disease seen in dermatology practices26

- General dermatologists treat patients medically and perform many surgical procedures

- Teledermatology has become increasingly common as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic28