GLOSSARY

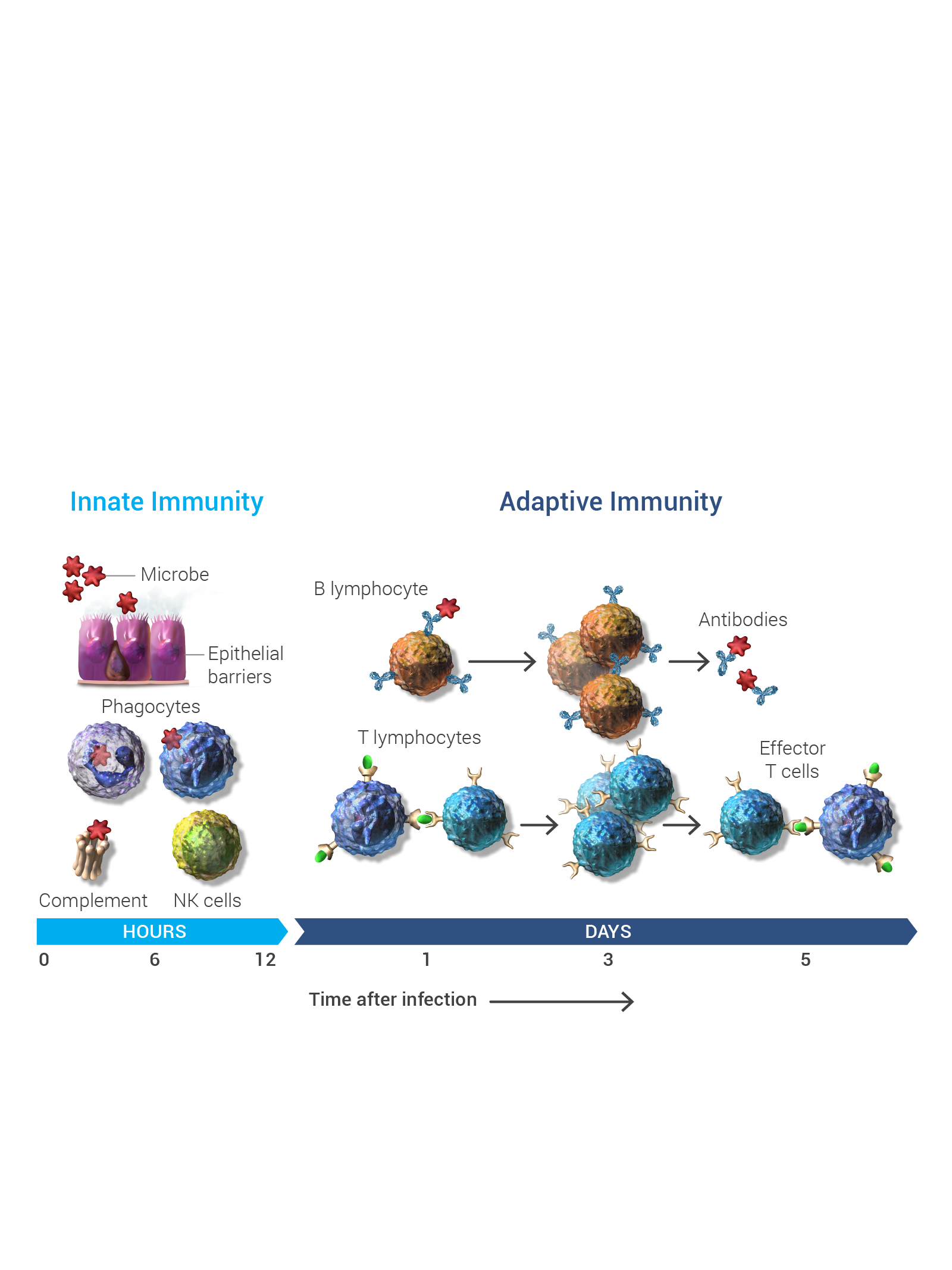

adaptive immunity: component of immunity which is pathogen-specific and creates memory

aminotransferases: enzymes that transfer an amino group from one molecule to another; aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase are frequently measured liver enzymes

antibodies: substances produced by B lymphocytes in response to a specific antigen

antigen: substance capable of eliciting an immune response or of binding with an antibody

antimicrobial: refers to a substance that either kills microorganisms or prevents their growth

autoimmunity: body's tolerance of the antigens present on its own cells, ie, autoantigens or self-antigens

B cell: lymphocyte which synthesizes and secretes antibodies

B lymphocyte: lymphocyte formed from stem cells in the bone marrow which migrates to the spleen, lymph nodes, and other peripheral lymphoid tissue where it comes in contact with foreign antigens and becomes a mature functioning cell; B cell

basophils: granulocytic white blood cells; essential to the innate immune response of inflammation because they release histamine and other chemicals that dilate blood vessels and make capillaries more permeable

bilirubin: orange-colored or yellowish pigment in bile; it is derived from hemoglobin of red blood cells that have completed their life span and are destroyed and ingested by the macrophage system of the liver, spleen, and red bone marrow

complement: group of proteins in the blood which play a vital role in the body's immune defenses through many interactions; acts by directly lysing (killing) organisms; by opsonizing an antigen, thus stimulating phagocytosis; and by stimulating inflammation and the B-cell–mediated immune response

cornea: transparent front portion of the sclera, about one-sixth of its surface; in front of the aqueous humor, the iris, pupil, and lens of the eye; first portion of the eye that refracts light, it is composed of five layers

cytokines: one of over 100 proteins produced primarily by white blood cells

dendritic cells: antigen-presenting cells that help T cells respond to foreign antigens; circulate in the blood and are also found in epithelial tissues, among other tissues

eosinophils: white blood cells with a lobed nucleus and cytoplasmic granules; contribute to the destruction of parasites and to allergic reactions by releasing chemical mediators such as histamine

epithelial: pertaining to the layer of cells forming the epidermis of the skin and the surface layer of mucous and serous membranes

immunoglobulin: one of a diverse group of plasma polypeptides that bind antigenic proteins and serve as one of the body's primary defenses against disease

innate immunity: immune defenses against infection and cancer which are not determined by the specific responses of B or T lymphocytes

leukocyte: one of several forms of colorless or nearly colorless cells of the immune system that circulate in the blood and lymph

lymphocytes: white blood cells responsible for much of the body's immune protection; include B cells and T cells

macrophage: monocyte that leaves the circulation and settles and matures in a tissue

major histocompatibility complex (MHC): group of genes on chromosome 6 which code for the antigens that determine tissue and blood compatibility

malignant: worsening or resisting treatment; said of cancerous growths

mast cell: large tissue cell resembling a basophil; essential for allergic and inflammatory reactions mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE)

memory cell: cell derived from B or T cells that can quickly recognize a foreign antigen to which the body has been previously exposed

microenvironment: environment at the microscopic or cellular level

monoclonal antibody: form of antibody, specific to a certain antigen, created in the laboratory from hybridoma cells

monocytes: mononuclear phagocytic white blood cells; circulate in the bloodstream for about 24 hours and then move into tissues, at which time they mature into long-lived macrophages

natural killer cell: large granular lymphocyte that bonds to cells and lyses them by releasing cytotoxins; cannot be activated without previous antigen exposure

neutrophil: form of granular white blood cell; most common type of white blood cell

oncogenesis: pertaining to the formation and development of tumors

peptides: compounds containing two or more linked amino acids

peritonitis: inflammation of the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity

Peyer's patches: group of diffuse lymphoid nodules within the mucosa of the small bowel

phagocytes: types of white blood cells (neutrophils and macrophages) that ingest and destroy microorganisms, cell debris, and other particles in the blood or tissues

platelet: round/oval disk that is found in the blood of vertebrates; contributes to chemical blood clotting and to other aspects of hemostasis

stem cell: a type of precursor cell that can also give rise to identical precursor cells

T cell: lymphocyte which responds to specific antigens with the assistance of antigen-presenting cells (APCs)

T lymphocyte: lymphocyte which responds to specific antigens with the assistance of antigen-presenting cells (APCs); T cell

thymus: primary lymphoid organ located above the heart, near the trachea